This week, the sight of seven thousand ethnic Rohingya refugees fleeing Burma and Bangladesh, adrift in leaky boats on the Andaman Sea, was broadcast into our living rooms and was a stark reminder that currently there are more refugees on the move than since the end of World War II – around 50 million according to the UNHCR. This is a complex problem, beyond simple political sloganeering or any one country’s resources.

The story so far:

The Australian Response:

Successive policies both by Labor and LNP Coalition governments have morphed into the Border Protection (‘stop the boats’) policy where people seeking asylum are no longer detained on Australian soil but in offshore detention centres such as Manus Island and Nauru. Reports such as The Australian Human Rights Commission’s ‘Forgotten Children (February 2105) and the Moss Report have shone light on the extent of deteriorating conditions experienced by detainees in these centres. And it is now a year since Iranian man Reza Barati was beaten to death while in custody on Manus Island. It would take an imaginative government now to pretend that off-shore detention has been a success.

Of course policy-makers argue that it has served as a deterrent and ‘stopped the boats’. Such a policy is full of holes. Perhaps (but how can we sure), that the boats have stopped and where are the people who would have got onto the boats? They have not meekly returned to their countries of origin but are stuck in countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The problem has moved locations, pushed offshore but not solved. Cruelty as a deterrent does not prevent people fleeing violence or persecution. And does this ‘end justify the means’ approach permit numbers of innocent people being used as living examples to discourage further deaths at sea?

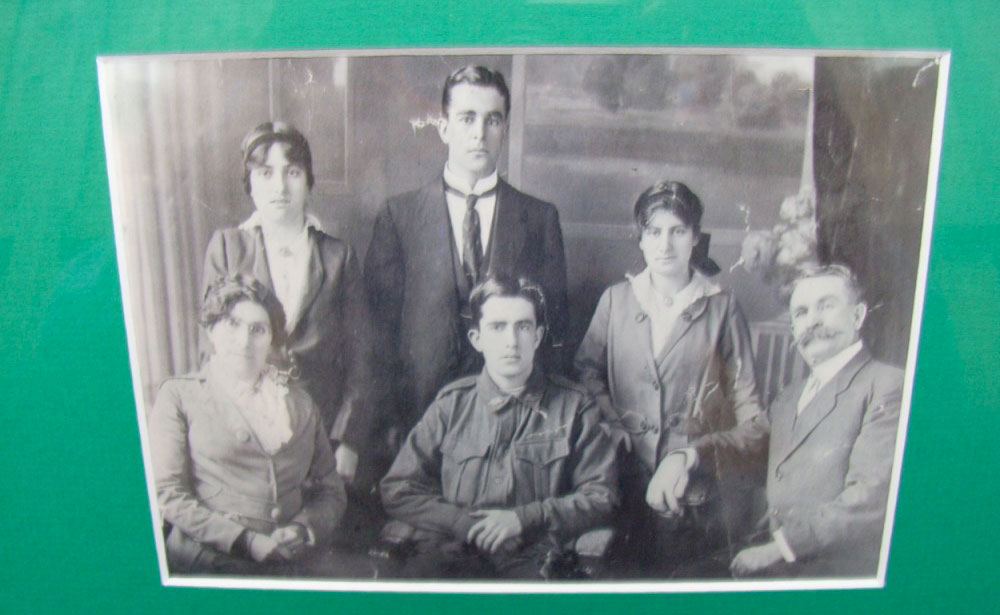

With our comfortable middle-class existence we, and our political leaders in particular, blindly urge an ‘orderly’ process’ for asylum seekers with neat phrases such as ‘front-door’ not ‘back-door’ and ‘please queue.’ Do we really comprehend what it means to flee from threats in one’s own country? I believe we have little understanding really. Desperate people will take whatever means possible to escape with their families from violence, persecution or crippling poverty. When I worked in Mindanao in the Southern Philippines in the 1970s I saw for myself how civil war drove people to leave their homes and take to a road of uncertainty, with little more than a handful of possessions, merely to save their lives. ‘Fight or flight’ is the gut response to approaching danger.

Economic refugees or ‘real’ refugees?

Public discourse now differentiates between ‘legitimate refugees’ and those who are merely ‘economic’ refugees, only seeking a better future for their families, not necessarily fleeing for their lives. While of course there will always be differing degrees of disadvantage amongst asylum seekers, I would argue that poverty too can be a form of violence. Economic refugees are not merely seeking to improve their employment opportunities or update their CVs, but are often fleeing crippling poverty that leads to death or chronic illness.

Unfortunately too the Government has repeatedly cut foreign aid from its budget since it came to office in 2013, with a $1 billion reduction announced in the overall aid budget late last year. The current 2015 budget has cut aid to Africa by 70 %, halved that to Indonesia and reduced by a further $3.7 billion over the next three years.

An Oxfam spokeswoman Joy Kiriakou recently said that ”these massive cuts to aid aren’t only the worst possible news for poor people, they are bad news for stability and they are bad and damaging for our international standing around the world.” It becomes clear pretty quickly that instability in these regions will only lead to further destabilisation and forced migration of poor people. Of course it could be argued that responsibility for poverty in any one country is just that, the responsibility of that country alone, but the question of Australia’s international responsibilities remains and is something I will touch on later.

A Borderless World?

Pakistani-born writer Mohsin Hamid, currently in Australia for the Sydney Writers’ Festival, posed some interesting and timely questions about whether we are moving into a borderless world. The notion of the pure nation-state is a relatively new concept, with modern nation-states, for example in Europe or North America, prospering in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and being promoted as a model form of governance. The creation of the League of Nations in 1919 and the United Nations developed the idea that the world is composed of a community of nation-states. But this remains a contested view, more an ideal than a reality.

The advance of globalisation and the subsequent dispersion of people all over the world has made the creation of the cohesive nation-state more and more difficult. In the past Australia, for example, given its relative geographic isolation, has made the task of gradually integrating new and ‘foreign’ cultures possible. However, in the face of millions of refugees on the move, can we retain this ‘orderly queue’ approach and cling doggedly to an ‘Australian’ purity model? Has migration now become a human right?

There appears to be a double standard under the encroaching influence of globalisation where wealthy, educated citizens can move unrestrictedly between borders as they please for employment and other opportunities while the poor, uneducated and persecuted find only enormous barriers wherever they turn. The opportunities of globalisation must be for everyone.

A Broader View

Dogged border protection policies in Australia have brought with them a resistance to, rather than an appetite for, international cooperation. Australia’s ‘head-in-the-sand’ approach to defending borders with a ‘law and order’ attitude, sees it trampling the international covenants it willingly signed in the United Nations and thumbing its nose at reprimands by international Human Rights commissions. As recently as today it was being brought to task by neighbouring Indonesia, who requested that we assist in the resettling of some Rohingya refugees. Indonesia’s foreign ministry spokesman, Arrmantha Nasir, said Australia was obliged to help as a signatory to the United Nations Refugee Convention. Painting ourselves into a jingoistic nationalistic corner does nobody any good.

New pressure points for refugees, whether in the Mediterranean or the Andaman Sea may gradually be coming to be seen as an international responsibility and impossible to deal with without both international and regional cooperation. It must be time for Australia to dispense with its short-term, three word sloganeering and reach out to both the UN and its neighbours to set up strong co-operative structures especially in South-East Asian refugee camps. ‘Go-it-alone’, insular policies have obviously failed. The government’s defence budget is to be boosted by $750 million in the next five years. This is no accident but indicative of an ideology to defend borders, withdraw foreign aid and resist international human rights agreements. This looks a lot like an Australia withdrawing behind borders and focussing on its own needs. In the long term is this an ideology worth pursuing?

This year the government plans to resettle 13,750 refugees and 18,750 by 2018, compared with 20,000 annually under Labor. Surely we could increase the number, given the thousands languishing in refugee camps. We could take a leadership role if both parties could commit to a more compassionate, take a more proactive responsibility and work harder to integrate such people into our communities with the help of nations in our region. ‘Operation Co-operation’ as a catch-cry even sounds better than ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ and may have a better chance of success.