Many reviewers have drawn parallels between the popular TV miniseries True Detective and the award winning Spanish film La Isla Minima (Marshland). In both a pair of unlikely matched detectives reluctantly take on the investigation of missing young girls and their possible murders. While True Detective is set in the Louisiana ‘badlands’, Marshland takes place against the backdrop of the Andalusian southern marshland town of Villafranco del Guadalquivi.

This film won ten Goya awards (the Spanish equivalent of the Oscars) and deserved every one of them. Directed by Alberto Rodriguez, the film is set in 1980 and follows two detectives, Pedro (Raul Arevalo) and Juan (Javier Gutierrez) searching for two missing teenage sisters. Considering that the dictator Franco died only in 1975, the period portrays brilliantly the murky post-Franco period of violence and corruption as the country tried to shake off the legacy and corruption of a dictator and move towards some semblance of democracy. It was a period known as the Transition.

Pedro and Juan are total opposites. The latter appears to be a product of the Franco military with a dubious reputation for torture, although this is left unclear. Pedro is younger, more idealistic and with his wife expecting their first child, optimistic about the future of Spain.

On one level this is a nail-biting thriller, a proper ‘who-done-it’ with car chases, a few punch-ups and plenty of shady characters. But it’s also much more. It’s a parable about morality, an exploration of how insidious corruption clings to an outmoded decaying system. How far can we humans go and still retain our humanity? What does it mean to be a moral and good person? And in the spirit an intriguing story, there are no clear answers.

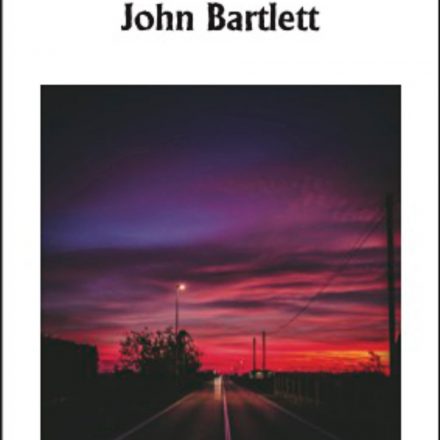

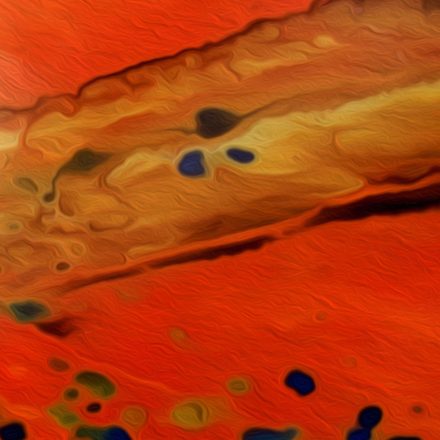

But the real knock-out star of this film for me was the landscape. Beautifully filmed by award-winning cinematographer Alex Catalan, the camera moves intimately over the faces of the actors and the breathtaking landscape alike. Both director Rodriguez and Catalan admit to having been influenced by the photos of the Spanish photographer Aya Atin whose portraits of the Guadalquivi marshlands inspired the mood of the film. According to Rodriguez, in the Aya portraits “there is always a background, always something more.” In this film there’s the lingering impression of what’s on the edge of the picture, just out of focus but having an insidious effect nonetheless.

Last year I was fortunate to visit this part of Spain and walked across the bridge over the River Guadalquivi in Cordoba. I was totally seduced by Spain’s landscape often reminding me of the dry northern parts of South Australia around the Flinders Ranges. But now after seeing this film I feel drawn too to the mysterious and ethereal landscape of the marshlands of the film. I was as it happened only two hours away from Guadalquivi.

At times the view in the film is from above, perhaps from the eye of an all-observing deity, giving equal witness to both the sins and the redemptions of creation. This birds-eye view displays patterns of marsh, river, crops and land overwhelming in their effect and not unlike depictions of indigenous dreamtime stories, where artists draw the contours of landscape, even though never having observed them from above. The film is truly a voluptuous visual treat.The camera is always in control, taking us at times into a widescreen panorama that seems full of possibilities and then switching to claustrophobic views of faces or tiny rooms that make us feel uncomfortable.

I’ve always felt ambivalent about films or stories that deal with violence against young women, which is at the basis of this story. It’s too easy to use the shocking details to seduce an audience, to sensationalise, to merely turn the story into a bit of soft-core porn. There is violence here but not I think for its own sake. This is a film which lays bare the insidious problem of corruption, of the misuse of power and of money and influence, an institutionalised misogyny that often takes advantage of people on the outside of society, of people struggling to make ends meet and to create better futures for their children. The issues here are universal and timeless. Violence against and slavery of women is currently a global problem. Films like this that lay these issues bare and try to ask questions and seek solutions are always to be welcomed. It just so happens that in the case of Marshland, it’s also a story created by artists at their best.