I was driving in traffic in Geelong this week and in the space of a half hour I (synchronistically) happened to stop behind two different Utes (surely the Australian emblematic symbol of a ‘real’ Aussie male) and I had time to compare their two divergent bumper stickers. The first read: ‘I’ll show you I’m a real Australian if you show me your Brazilian’ and at the opposite end of the scale: ‘Real Men Love Jesus’. I was confused. Which of these two aphorisms I wondered depicted the ‘real’ Australian male?

As Australians we’ve always had a quiet admiration for the characteristic larrikin, loudmouthed, beer-swilling, wheelie-performing male who never quite matures – boys stuck in the ‘Ute’ syndrome. But perhaps we are tiring of this cliché and demanding our ‘boys’ grow up a bit.

Reputations for manliness are generally what we apply to our sports heroes and in March this year there was an unprecedented outpouring of grief nationwide on the death of a football ‘legend’, Jim Stynes after a long and public struggle with cancer, but I suspect for something more than just his football prowess. (http://www.theaustralian.com.au/sport/football-legend-jim-stynes-dies-after-a-battle-with-cancer/story-e6frg7mf-1226304812859)

With Stynes, football expertise was only part of the story. The unexpected real grief that broke out in the community I believe had more to do with the fact that we knew an authentic role-model when we saw one as opposed to the fakes the media generally serves up to us – celebrity whatevers etc. Here was a man unafraid to show emotion and courage equally during his illness and in the face of an untimely death. His support for troubled teenagers became as legendary as his football skills. He demanded more of himself than mere macho bravado on the football field and he took seriously his role of helping disadvantaged young people to grow into their own maturity.

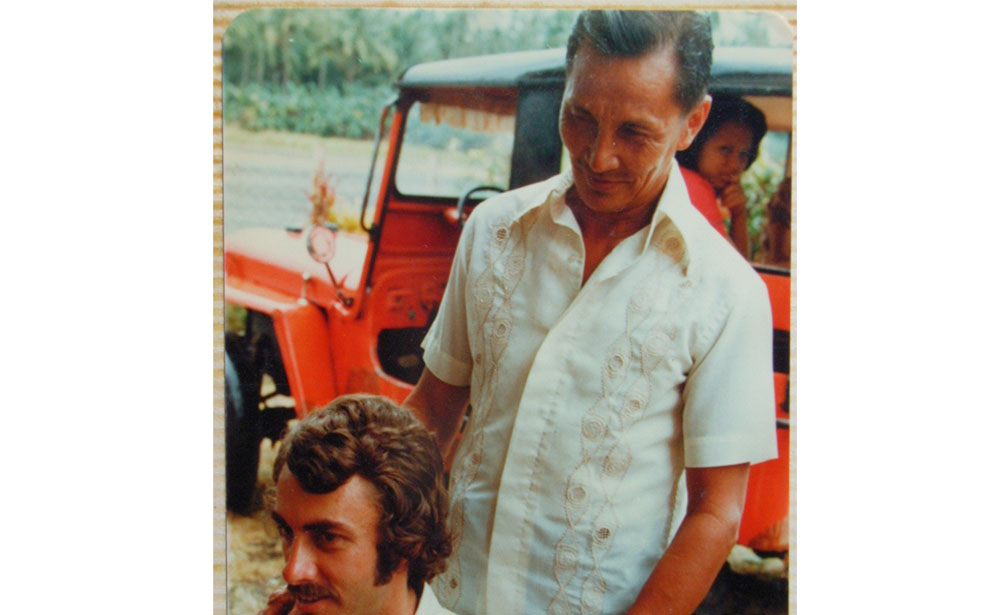

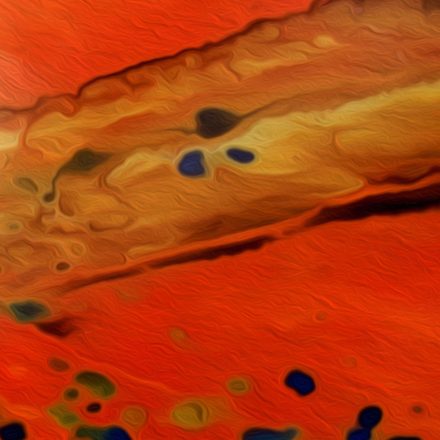

I had been thinking recently too about another man who was my friend many years ago and epitomised for me both what it meant to be a man and also to be a father. The attached image here depicts a younger me with my friend Isidro in the Philippines in 1979 on the day we said goodbye to each other, never to meet again face to face.

Isidro was a poor peasant farmer in the Southern Philippines where I worked for 9 years and one of the leaders in the small community prepared to stand up against the corrupt landowners and to struggle for justice. I think this photo depicts clearly the sort of man he was. As well as being a brave man he became some kind of a father to me at a time when my own father had just died so far away in Australia and I was unable to return home for his funeral.

Isidro was a poor peasant farmer in the Southern Philippines where I worked for 9 years and one of the leaders in the small community prepared to stand up against the corrupt landowners and to struggle for justice. I think this photo depicts clearly the sort of man he was. As well as being a brave man he became some kind of a father to me at a time when my own father had just died so far away in Australia and I was unable to return home for his funeral.

It’s only now looking back that I realise how gently and unobtrusively Isidro guided me when I was still learning how to become a man, having lost my own father’s symbolic as well as physical presence. In my novel ‘Towards a Distant Sea’ I recall Isidro and other leaders in the community, men who became role-models for me as a young man without the presence and example of my own father. Sadly now Isidro has long passed on but his spirit of bravery, kindness and steely determination looms more obviously in my conscious mind than it ever did in the 1970s.

Now at a time when our institutions, bedevilled by corruption, have failed to throw up satisfactory role-models for our young men, we must look elsewhere. These role-models do exist but they are not out there shouting ‘look at me.’ Young men deserve to get past the ‘Ute syndrome’ and to have the opportunity to learn from male mentors what it means to be a ‘real’ man.

Dear John,

Thanks for the reflections. I was lucky to have had my Dad till I was into my 60s. I only hope that I have been able to give our kids a bit more than utes. I’ll share your essay with them.

Well done John.

Frank Purcell

That made me laugh to begin with but then as I read on it was beautiful and moving. I think it would be good to achieve the balance…. I like a responsible larrikin…..like my husband completely hilarious and at the same time totally dependable! It’s an honour to meet people like your friend Isidro – thank you for sharing your story.

This poignant photograph is a strong counterpoint to the picture you have drawn of two heroes from different cultures, both men who would be good mentors for young men. By what authority so I, a woman, comment on male role models? That of a mother of a son, who was extremely grateful when she found men who were good role models for her son and now savours the results, a young man nurturing his own son with sensitivity, strength and laughter. The larrikin image is indeed no longer useful as it undermines the sense of responsibility which all humans, male and female, need to develop but I fear our media (and us consumers of that media) still focuces more often on the surface bravado of our sports ‘heroes’ than the values of those people. A thoughtful piece.

John, I enjoyed very much this piece about what it means to be a man and how you linked thoughts about one very positive local hero with a man from a very different culture who also has your admiration. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Thanks, John, for this perceptive comment on understanding masculinity in 2012. A beautiful photo captures vulnerability, companionship and strength in both of you. It prompts me to reflect on sonship and fatherhood in my own life. Inevitably questions bubble to the surface. Your comments and photo suggest to me that in accepting, our freedom to live in conscience begins to grow. So, a happy ANZAC Day to all as we muse on real mateship.