Not having played Aussie Rules football for more than forty years I’m not sure if the ‘holding the man’ rule still applies. That’s when you get penalised in a game for holding ‘the man’ with the ball for too long.

So the title of Tim Conigrove’s 1995 memoir Holding the Man was an apt description for the homoerotic love story between himself and footballer, John Caleo when they met as schoolboys at Catholic Xavier College in Melbourne in the 1970s. To the naive, the rough and tumble of the football world might seem an unexpected place to find a gay young man but of course with at least 2% of the population identifying as gay, we will be expecting more gay footballers to ‘come out’ eventually. The courageous Jason Ball has led the way. Gay people are everywhere, not just in those stereotypical roles assigned to us.

Tim Conigrove’s memoir (published posthumously) which I read and loved when it was first released, went on to be adapted to the stage in 2006 and has now been released as a movie, directed by well-known stage director Neil Armfield with a wonderful screenplay by Tommy Murphy.

This is a fine portrayal of a love between two people who just happen to be men, nothing sensationalist, or flag-waving here, just a tender, sexy love story that ends only in the tragedy of the two protagonists’ early deaths. Romeo and Juliet breathes its spirit through this story from the opening scene where Tim prepares for his role as Paris in that very play.

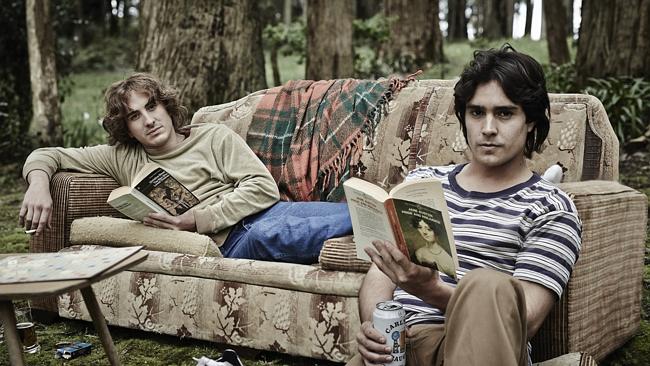

Tim is depicted remarkably well by Ryan Corr, possibly better known to Australian audiences as Coby in Packed to the Rafters. His energy and charisma imbues every moment of the story and he’s in nearly every scene. He’s a dynamo but well-matched by Craig Stott playing John, his lover. John is shyer, quieter, despite his football prowess, becoming as he did, in 1976 ‘the ‘Best and Fairest’ footballer in all the Public Schools of Victoria in that year. He is courageous in the stand he takes against his Italian/Catholic family’s grim resistance to the relationship. Kerry Fox, Guy Pearce, Anthony LaPaglia and Geoffrey Rush fill out an excellent cast.

LaPaglia I believe deserves special mention playing John’s father, a conservative man who cannot accept his son’s choices. It is a difficult, unsympathetic role and nowhere better portrayed as in a late scene where he confronts the two young men, his son already preparing for his early death and the father demanding that he ‘deserves’ a fairer share in his son’s will – a harrowing moment indeed.

The strength of this film I believe lies in the fact that it blows no trumpets, takes no moral high ground but where the simplicity and passion of the story is enough to silence any potential bigots. It’s a film that manages to feel authentic, evoking those years not so long past, when coming out’ demanded heroic energies. Anything political seems accidental here. There’s not a marriage equality banner in sight but there is an undercurrent, an unspoken plea that whatever skin one finds oneself in, you should be treated equally. It’s difficult to explain to anyone in the dominant heterosexual culture how powerful it is to see characters portraying your identity on the screen.

The latter part of the film is difficult to watch. Those confusing early years of AIDS when young gay men in particular were dying weekly are painfully evoked. Many of the hospice and hospital scenes are very confronting. I still remember some friends I lost in those years with their lust for life and wonderful talents, gone too early.

However, there are a dozen tender moments this film too. As for example when Kerry Fox as Tim’s mother and Tim are the kitchen preparing for Tim’s sister’s wedding the next day and slowly his mother comes to realise what an AIDS diagnosis will mean for her son.

Or Tim and John as schoolboys, forbidden to meet again, kissing through the fly-wire screen of John’s bedroom window – reminiscent, it has been suggested of the Romeo and Juliet balcony scene. Powerful and poignant images linger long after the credits have rolled by on this film.

The screenplay by Tommy Murphy, already a successful playwright, is full of Australian vernacular, authentic and funny at the same time. And yes there’s real gay sex on the screen too – passionate but messy and funny, much like everybody else’s sexual experiences.

This feels like a grownup Australian film and the tears that are an inevitable part of the experience, come from the fact that youth and indeed life are far too short that there’s real grief in the realisation that people do die too young and too tragically with dreams and passions only half-realised.

This is by no means a depressing film, nor is it a documentary. What lingers is the spirit of brave young men who only wanted to live passionate and loving lives and demanded to be accepted as they were. This is a film of hope about young people, their love, courage and how they lived the short lives they had with passion and wild enthusiasm. What more could we ask of our own young people?

Holding the Man is a film that has slipped imperceptibly into mainstream cinema and quite possibly will go on to become the Aussie equivalent of Romeo and Juliet.

Lovely review, very thoughtful.

Thank you.